Rosa F. Keller Library and Community Center

Located in the heart of New Orleans’ Broadmoor neighborhood—where flooding due to Hurricane Katrina was particularly devastating—the Rosa F. Keller Library and Community Center serves as a testament to a community’s recovery and the city’s evolving relationship with water.

LOCATION

SIZE

YEAR OF COMPLETION

CATEGORY

PERFORMANCE METRICS

SERVICES

AWARDS

PHOTOGRAPHER CREDIT

ASSOCIATED PRESS & PUBLICATIONS

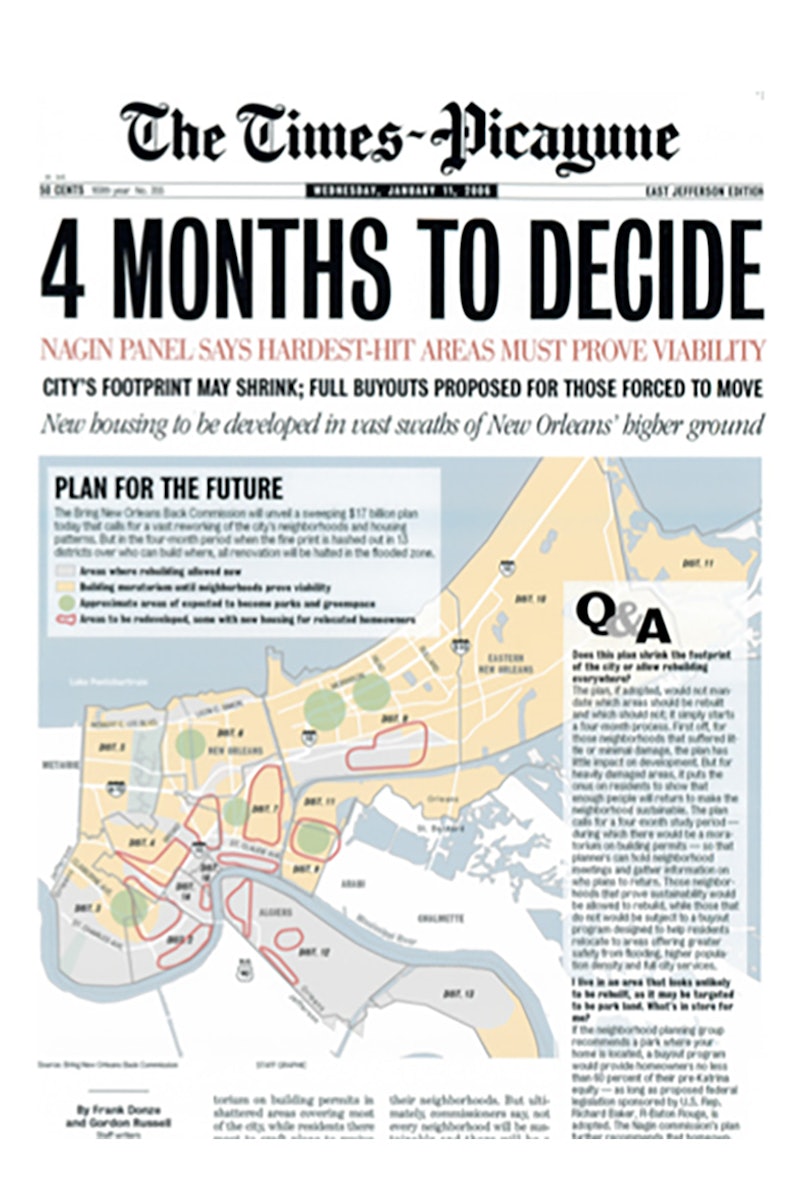

In the aftermath of Katrina, the Mayor formed a blue-ribbon commission that recommended a strategy for rebuilding the city. The plan was dubbed the “green dot” plan and identified certain areas of the city (those hit especially hard by the storm) as unsalvageable, and hence, not worth rebuilding. The Broadmoor neighborhood fell squarely within one of these green dots. Incensed by what they viewed as a betrayal by their own city, residents took it upon themselves to rebuild their community. EskewDumezRipple, working closely with the Broadmoor Improvement Association, secured funding for the first of numerous projects, the rebuilding of a library and community center to serve as the heart of the restored neighborhood.

The original 1993 library was inundated by the storm with over two feet of water. Though the historic home attached to it was less severely flooded, its structural integrity was compromised, its faulty foundation made poorer by the floodwaters. The ultimate decision came to demolish the previous addition, which many widely considered to be just that, an addition, and consider the site and historic home holistically.

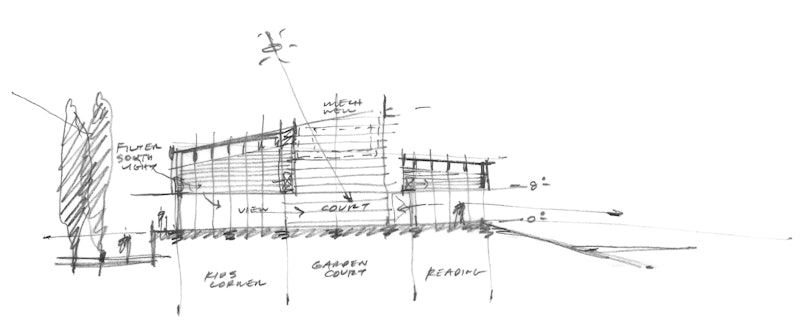

The design became a process of recognizing the inherent qualities of the original building and integrating its spirit in the construction of a new structure. Workshops were held with the local community in identifying the type of atmosphere the new construction should afford. Residents acknowledged a distaste for historic library designs as silent space, and envisioned a living space, where the community could come together for conversation, debate, and celebration.

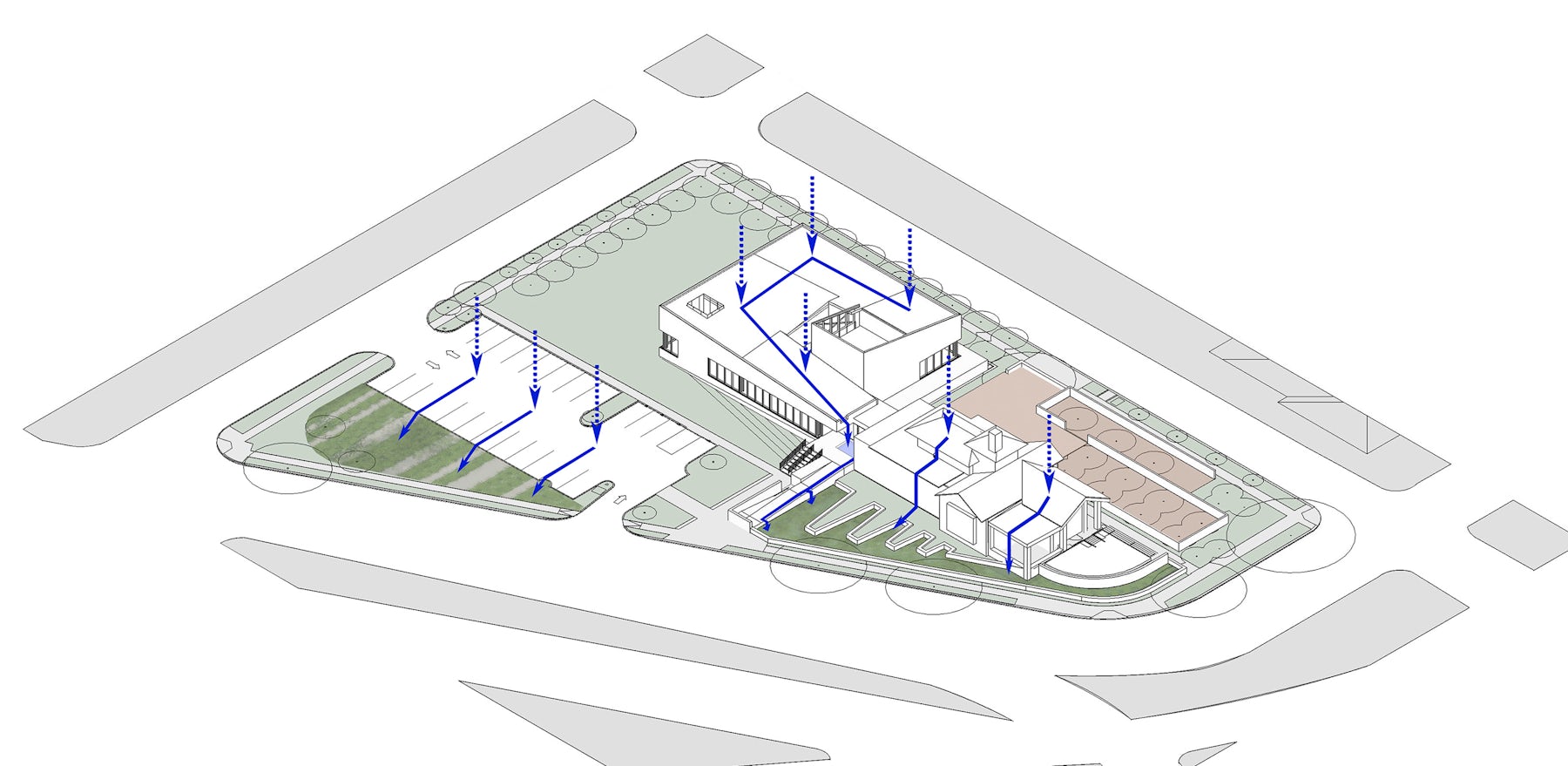

The structure today is one of seamless transition. Previously hovering on separate levels, the new design sought to unify the two disparate interiors. Raising the foundation of the historic home and creating the addition to match aimed to streamline the internal public space and mitigate the damage should another flood rise to similar levels. Paired with this internal community cohesion is the integration of active green space adjacent to the buildings. Retained from the prior design is an active play yard and exterior lawn for festivals or neighborhood celebrations. The design also endeavored to pay deference to the historic home. Pulling the original building back from the street focused the entrance to the home as a more prominent structural feature and unified the structure through a singular waypoint.

Perhaps it is no surprise that a community that suffered so much from the failure of structures designed to protect has become such a passionate advocate for rebuilding structures to endure. It was the community that insisted that the project pursue aggressive goals for sustainability and resilience, using the LEED certification process (recently attained) to provide a framework for validating efforts. Landscape and building form work together to manage the area’s intense and frequent rainfall events, using biological systems that mimic regional ecoystems, with a ‘river’ from the rooftop fed through a delta of wetlands that slow and filter the water, allowing it to slowly infiltrate back into soils—reducing the load on the city’s burdened storm water system and helping to reduce subsidence, a significant local problem. Nearly a decade later, the library, and the restored community center, replete with public gathering space and a rain garden, serve as a testament to community resolve and the role architecture and design play in urban revitalization.